During the conversations, I have with Design Leaders the question of how to manage difficult discussions comes up a lot.

These leaders find themselves managing many stakeholders and this often results in not satisfying someone, most of the time.

Although there is an individual need to make these discussions easier I think there is an organisation benefit as well.

The ability to handle difficult conversations well is a prerequisite to organisational change and adaptation. Businesses have spent the last twenty years focusing on process and technology improvements, and now there’s not much left to cut.

In the near future, breakthrough performance is going to depend instead on people learning to deal with conflict more effectively and, indeed, leveraging it for competitive advantage.

In the book Difficult Discussions the author’s research has shown that many of these difficult discussions can be distilled down to three questions:

1. The “What Happened?” Conversation.

Most difficult conversations involve disagreement about what has happened or what should happen.

What is the context of the issue?

2. The Feelings Conversation.

Every difficult conversation also asks and answers questions about feelings.

“Are my feelings valid? Appropriate? “

“Should I acknowledge or deny them, put them on the table or check them at the door? “

“What do I do about the other person’s feelings?”

3. The Identity Conversation.

This is the conversation we each have with ourselves about what this situation means to us.

We conduct an internal debate over whether this means we are competent or incompetent, a good person or bad, worthy of love or unlovable.

“What impact might it have on our self-image and self-esteem, our future and our well-being?”

I was recently introduced to a very powerful model of Alignment Coaching through ORSC Team Coaching training. I have given this a try a few times and so far am really happy with the results.

Alignment Coaching

The focus of the model is to achieve alignment not necessarily agreement.

The dictionary defines alignment as: “Bringing parts into proper relative position; to adjust, to bring into proper relationship or orientation.”

Alignment is always possible to the extent that people will avail themselves of it.

This is not the same as agreement or harmony. Alignment is about consciously agreeing to move in the same direction. It has to do with serving a common goal. To the degree alignment is present in a relationship, it is something that is coachable.

Mediation research (a really great intro to this is the book Getting to Yes) has found that one of the most effective ways to create alignment is to not engage with the positions(the solutions advocated for by one partner) but to find the common interests that lie behind the positions.

What this means is that even when the positions are locked, the interests or values behind the positions can still be aligned.

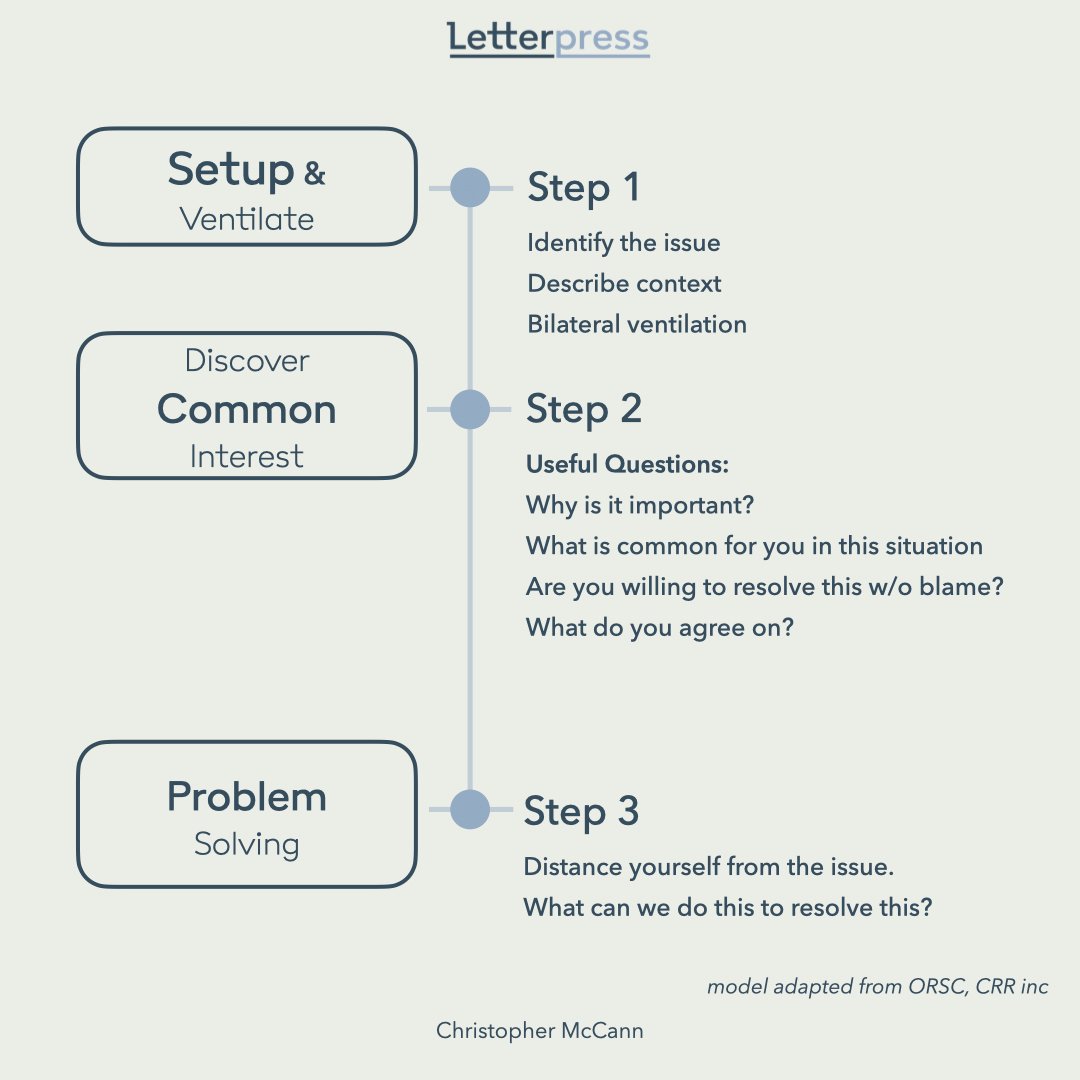

The model has 3 basic steps. Even though I have presented them in this order, the reality is improvising the order can also be effective:

Setup and Ventilate

During this step, the aim is to set the context and provide a type of clearing for the issue.

Each of the partners speaks directly to the coach rather than to each other.

Have the clients talk about how they feel about the issue as well as what they want to happen. Have them use “I statements.” This allows each partner to witness the other persons position and experience.

The partners speak to the coach and do not engage directly with one another, so they are less likely to escalate.

The coach’s role is to ensure a safe and balanced airing of the emotions.

The purpose of ventilating is to let the pressure out of a situation, so the relationship or situation doesn’t explode. During the initial part of this ventilation, the coach is much like a traffic cop, regulating the flow of the ventilation to be truly bi-lateral and ensure that everybody has equal time.

It is very common for blaming to occur. If this happens, ask the clients: “Are you willing to resolve this without blame?” and insist on it being necessary.

When they agree to it, really hold them to it! Coaching cannot effectively move forward while blaming is occurring.

Some good prompts:

“Why is it important to resolve this?”

“What do you agree on?”

Discover Common Interest

One of the ways to do this is to very simply reflect back to them the places where the coach hears similar emotional experiences or values.

“It sounds like doing your job well is important to both of you.”

“You are both frustrated with the situation.”

After reflecting the common interest back to them let them continue on in the discussion until you sense a shift in the energy of the conversation.

Useful prompts:

“What is common for both of your situations?”

“Why is it important to resolve this?”

“What do you agree on?”

Problem Solving

Once the clients have found some alignment try to give the relationship a word or find an object that can represent this (Post-its or anything object can work).

Move the object out in front of them (or give the object to the clients and ask them to do that together). Ask them how the issue feels now, so far away?

Very often when the issue is far away, the participants look at it more objectively and it loses impact.

Now that we have shifted how we view the issue, what can we do to make this disappear?

Ask the clients to brainstorm ideas that would move the issue forward.

My experience with using this tool is that is valuable in a couple of areas.

This is an alignment tool, not necessarily one targeted to getting to an agreement. I think when you remove this component the idea that someone will ‘win’ the agreement disappears.

The bilateral ventilation to a coach (as opposed to not to each other) is a great way of letting both sides communicate their view of the conflict in a neutral way. This is good way of reducing emotion between the parties.

I hope you give this method a try and good luck.